As it has just popped up on my personal Facebook memories that it is exactly 6 years since Konami were kind enough to share some work that I had produced on another website of mine, I thought I’d try and breathe some fresh life into the article.

Fans of Silent Hill always get mistaken by Centralia thinking that it is the sole inspiration for the series of games. Unfortunately they couldn’t be further from the truth. It is only the first movie that took some inspiration from the town and its history. Some years back, our writer Jonny Lupsha paid Centralia a visit with camera-woman Ashleigh Ellis in tow. What follows is his account of his visit.

Please note that the work on this page is not my own, I have kindly been given permission by its owner, Jonny Lupsha, to use it

Im sure that all true Silent Hill fans have heard that the first movie took inspiration from the real life town of Centralia, PA in America, but how much do you actually know of the area? Well, Jonny Lupsha and Ashleigh Ellis paid the small town a visit, and the following is the story they had of that day and the history of the town.

Jonny asks that if you read this article and like what you have seen to please make a PayPal donation to him, as he has made the effort to visit Centralia, come up with this piece for the fans and all off his own back. He is a regular guy like the rest of us and has a family to feed and clothe, so please make a donation of what you feel is fair to jonny.lupsha@gmail.com

At the bottom of the page follows a couple of other links for you

DisasterLand

Centralia

Words by jonny Lupsha

Pictures by Ashleigh Ellis

Words © Jonny Lupsha 2012

Pictures © Ashleigh Ellis 2011/2012

Released by A Carrier Of Fire

Heating

There was never a possibility that Centralia wouldn’t be a coal town, really. Originally co-founded in 1855 by the Locust Mountain Coal and Iron Company on a sizeable anthracite deposit in the mountains of Pennsylvania and officially instated as a town in 1866, it was destined to join its myriad neighboring towns – Ashland and Minersville included – in the mining industry. As a 1985 Penn State article said, “Throughout the century, coal companies played the determining role in building and directing the community. The townspeople were miners; the best-stocked store was the company store”. Centralia, nestled in Columbia County, had been home to over 3,000 settlers, mostly Irish, throughout the later 1800s.

The Locust Mountain Coal and Iron Company had gone so far with its influence over the town that it had, in efforts to control its workforce, helped to brew racism among Centralia’s residents against one another. This prejudice was harbored by segregating the residents by nationality – “Irish miners lived and worked in one area; the Ukrainian and Welsh and German miners in others”. Even the churches and graveyards are, to this day, separated along similar lines – Roman Catholic, Ukrainian Catholic, Greek Orthodox and Methodist.

Over the course of a hundred years, the small town population swelled until the anthracite business dwindled in the 1950s. With it went many of its residents, though in the early 1960s there were still over 1,500 people still living in Centralia and its immediate vicinity. It was an idyllic rural community, complete with a redbrick school building, a church with a steeple, locally-owned businesses and a small police & fire department office.

Today, nearly every building in town has been leveled and fewer than a dozen people remain.

Throughout much of 1935, a pit on the south side of Centralia’s Buck Mountain coal vein, near the Odd Fellows Cemetery, was painstakingly strip-mined. The remainder of the pit was left open and eventually used as a garbage dump.

In May 1962, a small fire in that garbage dump started it all. The fire spilled into an open coal seam and ignited a fire that spread underground throughout the borough and has been burning ever since. By July of the same year, 23 mines in the area had been forced to close. Almost immediately, local, state and federal agencies became involved in Centralia’s 400-foot underground mine fire, though their involvements have caused major controversy throughout the county.

The earliest action taken was by the Office of Surface Mining (OSM), a federal agency; and the Department of Environmental Resources (DER), a state agency of Pennsylvania. Accounts vary on the amount of money allocated from the government to save Centralia in the 1960s and ‘70s from its deadly underground fire, though the total is generally reported between $5 and $8 million. In 1969, the DER declared three families’ homes unsafe from high carbon monoxide levels and told the families to move. Throughout the 1970s, locals and government employees were unable to find a successful and cost effective method of stopping the fire. Relief was sought from The Red Cross, the Mennonite Relief Organization and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), all of whom refused to offer help. Since there had been no earthquake, flood, volcano, hurricane or other “act of God,” there was no way to label a specifically recognized disaster to the area. It’s likely because of this need for classification in bureaucracy that agencies like The Red Cross and FEMA refused to assist Centralia throughout its 50-year history of disaster.

Arriving at the Scene

I packed for most of the day on Friday, April 9, 2011, and left the house at 5:20 p.m. I’d suffered the hardest part of the trip before I even left: somewhere around 3 p.m., I realized how little I wanted to be away from the baby for three days. The longest I’d ever spent apart from Lenna was around nine hours during my old shifts at work.

Another 20 minutes and the Richmond skyline loomed overhead. Bank buildings and apartment high-rises reached upwards and I passed by them unnoticed. The flatlands of Richmond eventually gave way to the long, low mounds of I-95 North on the way to Tysons Corner. From our house in Chesterfield to Tysons Corner in north Virginia is a familiar, two-hour commute. It started raining, which I didn’t escape until I pulled into my hotel in Pennsylvania.

I passed Tysons around 7:30, having left I-95 for I-495 and passing Route 7, where we used to live. Just north of Tysons, a two-car collision in the right center lane caused a traffic jam that slowed the drive to a crawl. The next mile was a 20-minute stretch and it took nearly another hour to clear and break through into Maryland. The sun set, and a gentle dusk painted the sky muted oranges and crimsons.

I pulled over in Gaithersburg at about 8:15 and turned north onto a local highway. Had I turned south on it instead, for just a half-mile, I’d have seen a fancy seafood restaurant and a chain steakhouse. Unfortunately, all signs for the southbound lane of the local highway said I could only get back on the interstate heading south – towards home – from there, and I didn’t want to double back in such an unfamiliar place. I stayed with the northbound lane and headed towards a run-down part of Gaithersburg and an eight-dollar sub sandwich that fell apart a little after each bite.

A half hour later I was back on the road. The suburbs came fewer and farther between. Rural areas with ages-old warehouse and general store signs were peppered along the countryside. Every 30 miles or so I saw one large, brand new building – some deteriorating township’s final effort to bring in business.

Some people hate road trips, but they’ve never bothered me. I enjoy driving alone in a car and turning up music, or spending time on the road with my wife and daughter and discussing matters of no lasting import. Sadly enough, my lower lumbar and coccyx have been deteriorating since I was about 14 and since we’ve had the baby, that process has been expedited. Slouching in the driver’s seat reminded me every 20 minutes or so that my back isn’t what it used to be. I also never mastered comfortably keeping my foot on the gas for three to four hours on end, which sent aches moaning up through my right leg for most of the drive. Finally, I’d been rolling over onto my left shoulder in my sleep since I got a right shoulder tattoo in March, and holding Lenna almost exclusively in my left arm since she was born. This practice had led to some severe Tendonitis; if I moved my arm more than a bit in any direction, it shot a pain along my shoulder and into my bicep. All in all, my body was one big diagonal wreck of muscle and bone aches and pains.

As I drove, the car was a fingertip tracing a gentle caress up America’s cheekbone. Racing for the Pennsylvania state line, I came to Mount St. Mary’s University in Emmittsburg, Maryland. It looked dark and lovely since dusk had surrendered to the black of night. The campus is hilly and home to beautiful old stone buildings, and I had to wonder how many of its students, seeing it every day, considered these masterpieces to be old hat.

The number of streetlights and house lights waned as I crossed into Pennsylvania. Stretches of lightless road and forest appeared for the first time. The lights in the neighborhoods and towns along the highway became less uniform and more vertically graded; it was easier to see the same amount of lights than it had been in Maryland. I started to feel the distance from my house.

The last real city on the way to Frackville was Harrisburg. I guessed it was about half- to two-thirds the size of Richmond; its skyline boasted a beautiful domed capitol building and several practical skyscrapers.

Intersecting highways are a major fabric in any travel, and they’re always by numbers. I was already nearing my destination and, since leaving the house, I’d spent all of 10 minutes not driving on a numbered highway. 288, 95, 495, 270, 15, 581, 83, 81, 61. That was my lottery number for getting from my house to Centralia – 18.8 miles on this road, 54.3 miles on that one. It was 15 North that took me into Pennsylvania, and 581 East that showed me Harrisburg. No problem. The complicated bit is when a highway requires the driver to exit said highway to stay on it. After getting onto 83, I found myself taking three exits in 10 miles to stay on 83.

It was at that point, closing in on the last 45 minutes of the drive, that everything went dark. Night driving, of course, is dark to a certain extent, but this was like driving through the sky on a starless night. Coal black. The fog started to roll in, too. For a half hour, I saw nothing but the road in front of me. No cars. No lights. No radio antennae. The panic came in waves, then. Nothing strong enough to call a panic attack, but I could feel my heart pumping fast, my throat drying up. I thought back to the poorly-maintained buildings in Maryland. I found myself gripping the wheel a bit more tightly and looking forward to my return home. I believed those buildings, those signs of life, decorated Pennsylvania’s roadside as well – shabby houses were better than no indication of civilization. A quick flip of my brights could have solved the mystery and dispelled the fear, but it was easier to keep the hope I was not alone, and just not seeing anything or anybody, than it would have been to risk confirming I was.

I found myself incredulous of the notion that no other cars were in sight. This was a major interstate highway and the night was young. Fewer than 30 miles from my hotel in Frackville, the fog thickened and caught beams from oncoming cars in a heady cloud. It was only then that I saw the height of the mountainous range I’d been driving through.

I felt much smaller.

Still the fog thickened more. Every mile I drove towards Frackville it got worse. It was like it was coming from my destination, a beacon pulling me in. No matter how loudly I pummeled my ears with music, it still felt like too quiet of a night. By the time I turned off I-81 North at exit 124B, I could barely see the lines in the road. But I managed to check myself into my room at Granny’s Motel in Frackville around 11 p.m. without further incident and awaited Ashleigh’s arrival the next day at noon.

Granny’s has no central air or heating, nor does it offer ice, soap or shampoo. It does manage to offer free HBO and wi-fi, though.

As I settled in to sleep, I considered the irony that Centralia’s citizens wanted only to be left alone and not bothered by tourists and journalists, and I was going up there to do exactly that – despite the nagging wish in my brain to be at home with the baby. Even still, for better or worse, there I was on a Friday night, deep in Pennsylvania coal country until midday Monday, to document the fall of a little 160-year-old mining town that brought to history one of America’s strangest disasters.

I woke up in my room at Granny’s at 7:30 on Saturday morning, staring up at the water-stained stucco ceiling. Even before I got out of bed I felt the burning in my eyes and I stumbled to the mirror over the sink. My eyes were bloodshot; any cop in town would’ve thought I was high. I started retracing my steps, searching for what could have caused it.

I opened the contact lens case I’d placed next to the sink and my contacts were in it, so I hadn’t forgotten to take them out. Then it hit me.

It was the coal.

All the anthracite dust kicking around the local air for the last few million years wasn’t as friendly to tourists as it was to natives, and I was proof positive. I put in my contacts and it felt like someone had set my eyes on fire, but I’d left my glasses at home so I had to shut my eyes and bear with the burning for five or 10 minutes until it died down. While my eyes were shut I imagined what I couldn’t see: the third-rate carpeting under my feet, those peach-painted walls, the bathroom and the bright lights whose luminescence was only trumped by the white sky outside.

I felt my way to the shower and washed myself. When I could open my eyes I shut off the shower and had to walk dripping wet out to the main room. The bathroom was too small to dry off in; stepping out of the shower required an open door to get out. I thought with mild unease about the next two days – Ashleigh and I having to ask the other to turn around because we were coming out of the bathroom and had to get toweled off and clothed.

I was ready to leave by 8, but I didn’t want to make the drive to Centralia without Ashleigh, who was, in all likelihood, still in New York, probably passing by the city, so I blew an hour reading The Brothers Karamazov and playing video games on a handheld. At 9 I walked out of the room and was amazed at how foggy Frackville was. The door to the room was 20 feet from the road and I couldn’t see the far side of the street. There were rusted chain-link fences and industrial warning signs separating the motel from a small warehouse to the left of the room. Straight across from me was the manager’s office, which smelled like curry and was adorned with a terrifying 30-foot statue. The statue depicted a woman and a little girl, holding hands, presumably mother and daughter. The girl held a rag doll in her other hand. The paint, which was definitively a ‘50s or ‘60s pastel palette, was cracked and chipped and peeling off onto the parking lot; both the girl’s and the doll’s heads were missing, and had been for some time. To the right of the room was the rest of the motel – two floors, maybe 20 rooms, and four cars in the lot, including mine.

The fog was relaxed, motionless. In the following three full days, it neither drifted nor thinned. Indeed, it was as much a part of the natural landscape as the trees or the hills on which they sat. I was sure I could reach out and hang a fishing hook on a piece of fog and find it there the following day.

Despite being mid-late April, the temperature only hovered between the low 50s and mid-60s during the day, and dipped down into the 40s at night. Besides the fog, I was struck by how quiet the town was. When I’d arrived and unpacked the car the previous night, I assumed the quietness was just the small town’s lack of a wild nightlife, but during the day the silence was just as deafening, if not made more so by the fact that it was a Saturday morning. Just one car drove by every two to three minutes.

I made a quick trip to the mall to browse stores and waste time. Salesmen at GameStop recommended Vito’s Coal-Fire Restaurant in nearby St. Clair. “Just go back east into town, then south. It’s on the left; you can’t miss it.” Ashleigh called then, and said she’d just gotten to the mall. I had hired her a year before for this project and after plenty of hemming and hawing we finally set a date to go to Centralia.

Panic hit. What if there was nothing there? I thought. What if we’d moved around both our lives’ schedules and budgeted several hundred dollars each and we got to Centralia and all that stood in its place was some empty field? Shit; maybe I should’ve scouted it out after all. She’s an urban exploration fan back in New York; I come from a family whose idea of “roughing it” is staying at a Ramada. Could I make a convincing project leader in the smoldering ashes of a Vietnam-era industrial nightmare?

Then I saw a raven-haired young woman sticking out like a sore thumb, in a small fall jacket. She sat on a bench, her dirty sneakers pointed nervously at each other, staring at – and being stared at by – the local teenagers in their ill-fitting gym shorts and oversized sweatshirts. I stifled a laugh at our whole situation and knew I was blending in about as well as she was. I wore band t-shirts and blue jeans every day of the year. Ashleigh and I were freaks in rural Pennsylvania, but now there were two of us.

We bee-lined for Vito’s, which seemed about as local as we did. It has the atmosphere of a chain restaurant with money to blow, like a Macaroni Grill or Olive Garden, but with a clear and intentional locally-utilized niche – nearly everything on the menu is cooked over a real coal fire from local anthracite. It was as sleek and clean and modern as we were likely to get between there and Philadelphia, complete with a stone-and-wood interior and a fireplace burning. A full bar on an island in the middle boasted an impressive array of boozes from top- to middle-shelf. We had calamari to start and hoagies that had been toasted over the coals.

Back at Granny’s we prepped for the trip. I packed my messenger bag with a small laptop, an HD video camera, a digital still camera and my smartphone. Ashleigh grabbed both her cameras and a small satchel stuffed full of things I’d never understand, ranging from lenses to make-up. When we were all set we got back in my car and headed west and north on Route 61 to Ashland, passing the mall on the way. Ashland reminded me of Lake Galena in Illinois; it was one big gently-sloping two-mile hill with a four-lane road through the middle of it and stores and houses on either side. The road was Route 54 and we headed west up the hill and through town. I drove past the library and made a mental note to return later for research materials, and past a restaurant called The Drunken Monkey, which I’m ashamed to say I never visited.

I turned right onto 61 again, which resumed its northern course two miles west from where it dead-ended in Ashland. The fog through Ashland was considerably lighter, likely due to the traffic and slope of the hill, but it made no sign of disappearing altogether. It thickened again as we neared Centralia. Neither of us had the slightest idea what to expect.

A road sign read “CENTRALIA – 2 mi.”

“Alright, here we go.”

A sharp, sudden right turn on 61 surprised us both – so much so that as I hit the brakes and slowed from the 55 limit to 15 to take the turn, I almost had to turn wide and go into the oncoming lane to avoid flipping the car. It was as if the road crew had built 61 North not realizing there was a 10-foot dirt hill in their path, or not caring, and later chose not to bulldoze it. Immediately after straightening the car out, I had to correct again – the road arced left almost as suddenly as it had turned right, though now that we were only going about 20 mph it didn’t seem nearly as dramatic.

“Jesus,” I said.

“Right?”

61 came out of the S-curve facing northeast and soon we veered left to go onto Catawissa Road, which then dipped down. Catawissa changed names to Locust Ave. We approached an intersection with a four-way stop sign and saw a Ukrainian Orthodox church ahead of us, atop another large hill. Empty fields immediately surrounded the intersection on all sides. The street signs said we were at Locust Ave. and Centre St. We agreed Centralia was on the other side of the hill, just north of us, and the road came up and around to the right of the church as we talked about what we’d researched. We saw a stable with two healthy mares and a red pickup, and several other non-descript buildings peppered the road for the coming miles. Suddenly we were in the middle of a rural area similar to Frackville.

“Would a town with a population of eight people have 20 houses?”

“I kinda doubt it.”

“Shit; we took a wrong turn. Let’s go back to that intersection.”

We doubled back on Locust, passing a sign that said “CENTRALIA – 1 mi.”

“It must’ve been just to the left or right on Centre,” we decided.

When we hit our four-way stop intersection again, we made a right. Everything around the intersection looked the same, so I was trying my best to keep it straight in my head. OK, I thought. We came up north from Ashland, hit the S-curve and went northeast, then north, to the intersection. We went too far north past the church, doubled back south and turned right – west, rather – which would’ve been a left turn when we first came up. We hit a dead-end almost immediately.

“Well, we came from the south, hit a different town north and a dead-end west. I guess that kinda narrows it down?”

“If it’s not to the east, you’re the worst driver ever,” Ashleigh said. “Your directions are so bad you made a town disappear.”

We turned around and went east almost 10 miles on Centre St. before deciding we’d taken a wrong turn somewhere. A couple miles before we made it back to the all-too-familiar intersection we saw a sign that said “CENTRALIA – 3 mi.” Confusion set in, then frustration.

We parked at the southeast corner of the intersection. We had passed a little building with a fire truck parked beside it on our way through the first time and decided to stop and ask directions, or at least get the address from it and do a GPS search. On our way to the building, we passed trash heaps and several intersecting alleys, but the only thing between the alleys was dead grass and more garbage with the occasional pile of rocks or bricks. We couldn’t put our finger on it, but there was something strange about it.

Then we got to the lone standing building and read the words above the front entrance.

BOROUGH OF CENTRALIA FIRE DEPT. AND MUNICIPAL BUILDING.

Ashleigh spoke first. “Jonny…”

“Yeah?”

Ashleigh turned back to the intersection. We’d thought the roads led to nowhere, but Ashleigh saw it first.

“This is it. We’re in the middle of Centralia.”

As my gaze fixed to look at the entire view, it started making sense. We were standing at a firehouse and town government building. From its front door, looking northeast, we saw the intersection and I had a flashback of an ex-girlfriend’s rural New York town, which was really just one intersection itself. Here there were two churches (the second was hidden from view by a gravel pit we had seen at the west end of town) and what turned out to be four cemeteries. One church, the Ukrainian Orthodox building just northwest on Locust, obscured the first two graveyards; the hidden church, the St. Ignatius at the southwest corner of town, was home to two more – the Odd Fellows Cemetery and St. Ignatius Cemetery. The alleyways by the parked car used to be streets. The bricks were probably what were left of torn-down homes, and I’d be willing to bet that under the trash heaps were disturbed earth and, beneath that, hushed by soil and dead leaves, utility pipes and wiring. And underneath that, there was only the fire.

It was like a footprint – more a skeleton than a town.

Transition; Degradation

In 1980, the Centralia problem began to make much larger waves when the DER condemned 27 more houses. The following year, on Valentine’s Day, a 12-year-old boy named Todd Dombroski fell into a sinkhole that opened under his feet in his grandmother’s backyard. His cousin raced to his aid and pulled him out. An article in a local paper, The Pottsville Republican, recounts Todd’s story.

“Todd said he noticed some steam coming from the yard and went over and brushed away some leaves because he thought someone had thrown a lighted match and caught the leaves on fire. ‘The ground just started dropping. I went down to my knees then my waist and I just kept going down. I grabbed onto some roots and was screaming for Eric. I couldn’t see him and there was smoke everywhere. I heard him screaming for me to put my hand up and then he grabbed me. It was real hot and it stank and it sounded as though the wind was howling down there,’ he later added.” (Coleman, “Subsidence”)

Within a week, news of the boy’s near-death experience spread worldwide and pressures mounted for state and federal governments to act as situations deteriorated in Centralia. The local baseball field was last used in 1983 as visiting teams refused to play games near the fire and its poisonous gases.

A local group called the Concerned Citizens against the Centralia Mine Fire (CC) formed following the Dombroski incident, bringing further media attention to the town. Most members of the CC were reported to be young adults and frantic parents who lived on the side of town closest to the fire at the time, and residents across town disapproved of some of the more negative attention being brought to Centralia.

From December of 1982 to June of the following year, inspections of the mine fire were carried out by GAI Consultants, Inc., of Monroeville, Pennsylvania. GAI was commissioned by the OSM to determine as many factors about the Centralia blaze as possible. The GAI report states that “if left uncontrolled, the fire could conceivably spread over an area of approximately 3,700 acres,” an area that encompassed Centralia, Byrnesville and Germantown, PA.

The 3,700-acre potential reach of the fire is partly due to the “complex interrelationships of geology, mining and hydrology” in the area. Further, GAI claimed that anthracite mine fires are “extremely difficult to control because of multiple-seam mining, steep dip of the coal-bearing strata and other complicating geological phenomena, cross-seam rock tunnels and drainage galleries and highly fractured rock strata,” all of which were present in Centralia.

The basic idea of layers of geological strata is similar to a layer cake. Over millions of years, as the Earth’s environment evolves and changes, different layers of sediment collect, each telling the story of a different era of time, like a hyperbolic ring around a tree. Seismic disruptions like earthquakes or volcanoes can fracture an even bed of earth, causing one side or the other to slide downward and become uneven with the other. As the coal seams have grown through one or multiple plates of earth, often becoming more complex as they grow, the area looks less like a smooth layer cake, or layers of skin, and more like a compound fracture or scar tissue – broken, reassembled, broken again and reformed. These factors and more seem to have prevented GAI or the OSM from easily cutting off the fire’s oxygen and coal supply the way one would plug a hole in a pipe or tourniquet a vein.

The GAI geologists also determined that the coal fire could burn for more than a century if left alone. The report presents several options, based on cost effectiveness, of relocating Centralia and Germantown and/or digging perimeter trenches to stop the fires from spreading.

These findings, published in July 1983 by the OSM, sparked the majority of the government involvement in Centralia – though some questioned the government’s motives, due in part to other findings in the GAI survey.

A complete excavation of Centralia would cost over $660 million. Digging the largest single trench, Trench A, would likely isolate two-thirds of Centralia from the fire and constitute about 8.6 million cubic yards of digging. The cost for Trench A was estimated at $62 million, roughly 10 percent the cost of a total excavation. Curiously enough to some Centralians, the section detailing the digging of Trench A is bookended by two passages about cost-effective land procurement: one on buying land and property from Centralia and Germantown homeowners, the other presenting an option justifying isolating the fire from Germantown, but only “if protection of the coal reserves is also an objective,” and that Germantown “would be protected from the Centralia mine fire as a matter of course”. To some residents, this sounded like the government was saying they could buy private land, rid themselves of the homeowners, stop the fire and keep the anthracite coal rights for a mint – that “protecting the coal reserves” was for the government, not the homeowners. If the fire was a danger, and that was the reason for the excavation and evacuation, why present options whether or not to extinguish the fire? Why refer to protecting Germantown as a “matter of course” – something that would just be a happy byproduct of the excavation when it was meant to be their main concern?

In October of that year, the U.S. Senate approved an expenditure of $42 million by both federal and state governments to buy out and relocate Centralia residents – by this time, over 20 years into the fire, the population had shrunk to about 1,000 citizens (Ruane A1). Many of them happily accepted the government checks and moved away, and demolition of government-owned homes began in December 1984. By this time or shortly thereafter, the town’s only doctor had died and nearly all its businesses had shut down – barely a store or restaurant remained.

However, there were many holdouts once the 1983 buyout was approved, and it is around these holdouts the controversy centers. The GAI findings and the inability to label Centralia as one kind of problem or another even led to some of the borderline mass hysteria among the town, thus creating an almost new breed of Locust Mountain Coal’s segregation. Factions seemed to appear depending on residents’ beliefs about the coal fire. One Penn State sociologist, Stephen Kroll-Smith, observed, “Depending on your immediate experience of the fire and your confidence in the government’s information, you developed a set of beliefs about the risk. These beliefs became more important than the evidence. People took their beliefs and used them as points of departure for talking about the fire. And they didn’t trust other people’s stories”.

Kroll-Smith even conducted a study with colleagues and found that the main source of stress among Centralians wasn’t even the fire but all the arguments among neighbors and residents. Town meetings with guest representatives from government offices ended in screaming matches and chaos.

Shortly after the government buyout began, Penn State researchers including Kroll-Smith spoke with remaining Centralians and found that a full third of them believed the fire was kept alive by a government conspiracy to swindle the residents out of the coal under their feet, likely a theory fueled in part by the July 1983 GAI report regarding trench-digging. “They know how to put this fire out,” one resident told them, “they’re just experimenting with us”. Residents at the time had estimated 35 million tons of anthracite coal under Centralia. Selling at $100 a ton, there could be over $3 billion in coal still waiting to be excavated. Some residents believe this is the true reason they were offered $42 million to evacuate once the GAI report was published, which would severely undercut a full excavation and allow for minimal governmental risk of increasing overheads. Locals believed that if the government fully bought and evacuated the town, even spending an estimated $60 to $80 million for trench-digging to stop the fire – which, officials had always told the residents, was “too expensive” – the government would be sitting on billions of dollars of coal to mine at the government’s leisure.

As time drew on, things got ugly. Government officials continued to argue with one another and with Centralia residents over the fire’s location, source and other factors. The government’s relocation offers started sounding more like threats to Centralia’s holdouts, most of whom dug in deeper, though others scared and continued to relocate. The standoff grew. News cameras rolled in; university students began to poke around to study the town for class projects.

Back in the 1980s, across an alley from where Todd Dombroski nearly fell to his death, two families had refused the government’s offers and their houses stood alone. One woman’s backyard, from which the highest temperatures of Centralia’s fire were recorded, was photographed with her husband pulling carrots out of their garden. The carrots had been cooked in the dirt by the fire (Ruane).

One story of a Centralia couple in 1987 reads, “a 65-year-old man killed his wife and then himself after the state began working to relocate the couple, who were renters in a house the government had just acquired” (Ruane).

Physical Evidence, Phase One

From the stories of children falling into sinkholes, earth on fire, a murder-suicide, billowing smoke and seismic torment visited onto this town, I really expected some cartoonish wasteland befitting a post-apocalyptic survival movie. I realized at once the excitement I would’ve felt is shameful, and the deflated outcome of the town and my expectations didn’t breed disappointment in me, but an overwhelming sadness that didn’t hit me for over an hour.

By the time we’d decided to start gathering research material, it was well into the afternoon. We tried a field west of the police and fire building with no luck and started back where we’d parked, in the middle of a flat alley that led to a woody dead-end. Ashleigh took pictures of plots of land where houses had presumably stood, dead grass and weeds sprouting from the dirt like fireworks. I was almost disinterested, at first.

This isn’t a town. It’s just…it’s nothing anymore.

After what felt like an eternity we crossed a small road to a hill full of thin trees. Then I saw, in a cement lot, a vertical steel pipe with a backboard from a basketball hoop near the top and I realized I was standing in someone’s childhood playground. The intense smallness of the area gave way to a foreboding loneliness in me, which was compounded when I wandered off up another short alley and saw my first Centralia home buyout.

I almost didn’t notice it – there were so many birch trees I almost walked past it.

Then I noticed three small cement steps. Front steps. At their top was a small, flat square of cement – what was once a front stoop.

How many houseguests hopped up these stairs and knocked on the door? Did a mother sit with her infant on this step, telling her baby about all the neighbors before picking him up and going back into the house?

There was no front door. There wasn’t a house. The stairs led to nothing but a cement foundation, which gave a vague idea of the area of the house. There were as many birch trees in its perimeter as there were outside it; it looked like some idiot laid a foundation for a quaint rural home in the middle of a forest without realizing there were a hundred trees in his way. Ashleigh noticed it almost immediately and came over to take pictures. We’d never know who owned the house, where they are now or even what the address was. It was akin to a John Doe crime scene victim, but even further removed from life.

There were more all around it. Some father’s weekend project repainting the shutters was now a moot point, and I walked to the next house. We tried to imagine the linoleum or carpeted floors. Growths of trees almost faded as we pictured thick couches and old TVs.

Revving ATVs and motocross bikes snapped us back to reality. We hadn’t considered running into any real opposition in town – I would’ve been amazed to see an actual resident – so I was more at a loss for words than anything else when a small team of off-roaders came ripping down a hill towards us. I gave a friendly nod down as they passed us, and judging by their body sizes, they were high school boys from a town or two over. They buzzed away and I thought both of us breathed a little easier.

Another block towards the intersection, we started to see mounds of trash – new trash and old trash alike – where the houses had been as well as their front yards. We got closer to make sense of it, and it still took me several minutes to sort out the story. Suddenly I was back in Geology class at college.

The earth forms from the inside out – new rocks, new dirt, piled on top of the old.

At the bottom was the normal dirt and grass, which had only ever been disturbed by the eventual tearing down of the house. Leftover garbage from the original tearing down of the house – linoleum floors from the ‘80s buyouts, newer drywall from the ‘90s – rested on the ground. Apparently the trash collectors never bothered to pick it up. After that, what sat above those creature comforts varied from lot to lot as we walked down the street. Sometimes it was another 10 or 20 years of dust and dirt, grass and spider webs and anthills blanketing a mash-up of kitchen and family room. Other times, depending on the age of the buyout, it skipped that layer to the final addition to most of Centralia’s construction heaps: new trash. We found ourselves able to date the trash within a couple years based on the packaging of soda bottles, hamburgers and prophylactic wrappers. The familiarity of geological commercialism, wrapped comfortably in my cynicism, warmed me from the creeping feeling of Armageddon preying on the afternoon. We squatted next to a mound of plastic and paper.

“That Quarter Pounder is straight-up 1980s,” I said.

“How can you tell?”

“Styrofoam box. Original ‘polar bear’ Coke can on top of that; that’s early ‘90s at the oldest.”

Other time-telling junk included Monster Energy drinks, Crystal Pepsi, low-calorie beer, blank CDs and polyurethane condoms. There were also more cigarette butts than there were trees. Evening was coming in a few hours, and with it blew a cold wind. We couldn’t believe people were returning to Centralia and drinking, smoking, blasting music and having sex. It felt like walking over someone’s grave…but it was the town’s grave; it was Centralia’s headstone, and people had been coming here for decades.

We drove northwest to look at the Ukrainian Orthodox church, its ball-and-spike spire reaching far into the sky. It still held services, though the parking lot was vacant that day. Its two cemeteries were separated by ethnicity – the names on the headstones told us that much. The segregation was a 150-year-old signature by the Locust Mountain Coal and Iron Co. with very few exceptions to its arrangement. Some couples, buried together, had broken the racial boundaries as early as the late 19th century and I wondered if their parents and friends had a hard time with the interracial marriage.

Behind the Ukrainian church we spent some time exploring abandoned trailers with bashed-in toilet seats. Where once families had lived – one with little girls, judging by the scattered toy parts left behind – white supremacist graffiti adorned the walls and ceilings. Swastikas and racial slurs were everywhere. We both believed that neo-Nazis and wannabe Klansmen were more territorial and prone to violence than was nearly rational so we scurried through the trailers quickly.

We went back to the car and drove south, back to the increasingly familiar intersection of Locust and Centre, and stopped the car near the municipal building. A paved car path, wide enough for just one vehicle, led us west by southwest past St. Ignatius Church and its cemeteries to a series of gravel pits. We were about a half mile directly west of where the fire had first started in 1962, and we exited the car and smelled it immediately.

Sulfur.

A rustling caught the corner of my eye and I thought the air was getting to me because it looked like the grass and dirt were shifting slightly. I walked closer and realized it was an impossibly small tuft of smoke – shorter than what would rise from a discarded cigarette butt. We continued to walk around, up and over and back and down and through several hills of dirt and gravel and rocks. Everywhere we went, the smoke got bigger and denser. It was like a warning sign – stay too long, and a fire will break out above ground. Eventually, just before dusk, we reached a smoke cloud that wafted 15 feet high. We raced the sunset with our notepads and cameras, getting video and photographs and notes of it – as soon as the sun went down and we lost light, it would be dinner and sleep time. We couldn’t stay too close to it; the sulfuric gas and carbon monoxide rising from the fire made us queasy after a few minutes.

My sympathy for the families whose houses were now rubble, along with our historical rigor, was starting to share a bit of space with excitement. We remained respectful and quiet and somber, but I was starting to realize why Centralians don’t like visitors. It was in all this gathering of clues and evidence, all this detective work, that I realized our position. We weren’t writing a story. We were compiling an autopsy report.

Decomposition; Oxidation

In 1990, residents of Centralia’s neighboring town Ashland began complaining of odors from the mine fire. This prompted the DER to install an air monitoring device for toxic chemicals, as the residents had in fact been smelling hydrogen sulfate coming from the subterranean blaze

As gases leaked out of the coal seams throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the fire has actually caused miniaturized versions of seismic drifts – much like those GAI claimed were complicating the fire’s extinguishing in 1983. The changes in temperature from the fire caused many depressions, buckles and breaks along Centralia’s Route 61 throughout the 1980s, and the highway was closed off and repaired frequently by the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation and the DER.

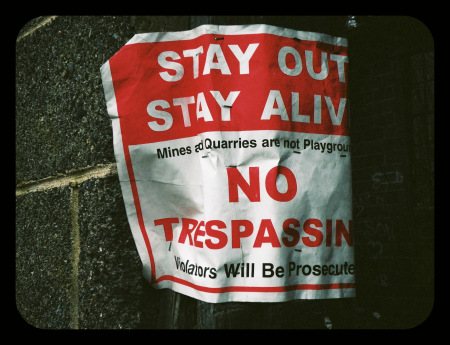

During this time, however, disaster tourists started to arrive. On Earth Day in 1991, buses arrived “with people running all over the mountain getting their pictures taken near the fire” (Coleman, “Tourists”). Besides the Earth Day troupe, strangers started showing up to see phenomena like the open flames that appeared along the troubled Route 61 at 25-foot intervals or so, burning straight up from the ground. Local experts, such as former Centralia emergency management coordinator Ray Reilley, expressed their concerns about sightseers who ignored the dangers of such events and places, opting instead to tear down warning signs and approach the fire-hot rocks that were placed to control fire eruptions. Soon after, Route 61 would close for good. Due to the minor geological and sedimentary shifts from the fire that had caused the cracks and buckles along one section of the highway, a bypass had become the main mode of transportation through the south side of town. A split along 61’s two-lane asphalt eventually became large enough that cars would never again be able to traverse its southbound side, resembling a broken-in-half chocolate cookie more than a road, and the highway was sealed off with signs, and eventually mounds of dirt were bulldozed to either end.

Amidst the tourists and the closing of Route 61, however, a moment of relief came to the little town of Centralia in 1991 when several federal agents came for a visit. A DER official declared they and other government officials would simply “watch and wait” over the fire for at least the next year, in hopes that it would burn itself out. One DER official, Steven Jones, resolved that “As long as there is oxygen in the air and combustibles in the ground, this fire is going to be there”. State officials still estimated the cost of completely digging the fire out near $600 million, and warned locals not to hold their breaths for that amount of money.

After a long stalemate between residents refusing to leave and the government pushing them to sell, it seemed everyone was happy to monitor the fire’s progress and simply repair any emergency that arose as a result.

When that year of watching and waiting was up, however, the state of Pennsylvania and the OSM reviewed the Centralia situation and decided to revise its position on the town. On February 18, 1992, remaining Centralians were issued letters by the law offices of Rosenn, Jenkins and Greenwald, of Wilkes, PA, stating that “the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania has made a decision to implement eminent domain proceedings in order to protect the safety of those who have in the past declined to participate in the voluntary acquisition and relocation program in Centralia and affected areas in Conyngham Township”.

So said one reporter, “For reasons of health and safety, [the state] was insisting that the remaining stayers accept compensation and leave. Those who declined would have their property condemned and seized”. To the holdouts, the requests had officially become orders. The state’s eminent domain decision had also been approved both by the federal government and the Columbia County Redevelopment Authority (CCRA).

The borough decided to take legal action in regards to two separate issues regarding the eminent domain proceedings. The first lawsuit they filed was against the state, the CCRA and the Department of Community Affairs (DCA) to protect holdouts’ mineral rights, echoing Centralia concerns since the 1983 GAI report was published. “Someone has been waiting very patiently to get their hands on this coal,” Anne Marie Devine, then-mayor of Centralia said (Loughlin). “We’re just not that gullible.” The DCA and the DER initially claimed that the dangers of the mine fire prompted them to set an original deadline to shut down the town completely by June 30, 1994, but later admitted this deadline was agreed based on the expiration of the original federal buyout program, which at the time was in August of that year (Loughlin). Furthermore, residents and Centralia officials argued that if the town were to be completely shut down by the state, it would legally cease to exist and therefore its coal rights would escalate to the nearest body of government – the very state offices forcing them out. This lawsuit was dismissed by a Columbia County judge, though its proceedings delayed the borough’s shutdown past its June 1994 deadline.

The second lawsuit filed by residents, which also delayed the forced evacuation of the town, was brought by 38 homeowners against the OSM, disputing specific parts of the eminent domain proceedings unrelated to the mineral rights or the first lawsuit. That lawsuit was also dismissed by the Columbia County Court, in February of 1994, and in 1995 the Pennsylvania Supreme Court turned down their appeal.

The remainder of the story of Centralia’s population is one of reduction. By the time Route 61 closed, only 60 people remained. During the legal battles over eminent domain rights, the government began the process of taking ownership of all Centralia’s properties, including its homes. The OSM formed the Centralia Task Force, who sought to use regulated condemnation proceedings to quickly obtain Centralia’s properties. This caused even more residents to move away.

Despite fighting for over a year in court, 14 holdouts gave up and left Centralia for good by 1993, including former postmaster and borough president Molly Darrah – a lifelong Centralian. “I thought I’d live and die in Centralia,” Darrah said. “We fought it long and hard…but we couldn’t win it. They wanted us out…I had no choice. I learned to accept what I cannot change.”

Finally, the late 1990s served little respite for the borough. The state of Pennsylvania scheduled demolition of Centralia’s historic St. Ignatius Church for late 1997, having stopped regular service during Christmas two years prior (“Landmark Church”). Centralia’s Hubert Eicher School was razed around this time as well, after standing for 60 years. In 1998, Centralia was home to just 34 residents. The original federal buyout program (which had been delayed for several years) finally expired, and as of 2012, the courts are still attempting to force the last dozen or so Centralians out of their homes.

The population today hovers near 10.

Physical Evidence, Phase Two

Sunday morning we got up and paid a quick visit to the local Frackville diner before spending most of the day in Centralia. Two dollars in quarters bought me a listen to 10 songs on the jukebox while we ate breakfast and marked off sections from maps we drew on napkins. The Locust and Centre intersection made a nice landmark for Centralia, cutting it into an even four plots of land. As it stood, we’d really only covered the southeast quadrant of town completely, where we’d seen the housing foundations, and the northwest corner with the Ukrainian church and graveyards. From the foundations, to our west was the police and fire building and to our north was a large empty field. We finished our food quickly and drove up there. After a quick stroll through the field at the northeast corner of Locust and Centre, we decided to spend most of the afternoon at the southwest corner of town – which had two more graveyards, St. Ignatius Church and one more surprise for us besides the municipal building and gravel pits we’d seen already.

One of the times we drove north through the perilous s-curve on Route 61, Ashleigh had mentioned the highway that had closed down. We knew it was Route 61 that closed, but all the way until Locust and Centre, street signs saying we were on Route 61 stayed with us. Byrnesville Road was Route 61. Catawissa Road was Route 61. Locust Ave. was Route 61. On this occasion, though, when she mentioned it, it was like the piles of dirt that we thought had never been bulldozed started looking artificial. Maybe they were bulldozed to that spot, we thought.

It was too dangerous to park on that section of highway, even over on the shoulder, so we kept driving north to St. Ignatius Cemetery and doubled back on foot, south, to another plowed-in dirt hill that looked almost identical to the first one. We climbed awkwardly up the hill’s north face and peeked over to the other side.

The abandoned Route 61. The real Route 61. Some called it “Hell’s Highway.” We scrambled down the south face of the dirt hill and started walking down it.

We walked southwest on the old 61, towards the s-curve we’d navigated three or four times by now. We hadn’t seen the old highway from the stretch of road leading into Centralia – it would’ve been on our left, then – because of a high, earthen mound that had formed naturally and hidden Hell’s Highway from view. We realized we couldn’t have seen it from St. Ignatius Church or the gravel pits because of the woods and the sharp rock incline on the west side of the closed road – it was easily 30 to 50 feet before leveling out to heavy woods. It was almost completely hidden – like the cement steps leading up to nothing, which barely caught the eye, the bulldozed dirt blocking passersby from even seeing it was just a little funny-looking.

Graffiti covered the highway. There were probably 300 penises and 50 naked women, dozens of swastikas, stencils ornamenting offerings to Satan, poems, hippie quotes, song lyrics, girls’ phone numbers, video game references and couples’ initials inside big love hearts. We took a hundred pictures between the two of us. Fissures seeped smoke and sulfuric gas; the asphalt was unnaturally warm considering the biting chill in the air.

In the middle of the southbound lane, a seismic disruption had caused the asphalt to crack and split along the road. Gas and smoke rose incessantly from the chasm, which was several feet deep and hot to the touch.

We met a few cars of tourists, who I interviewed. They helped explain the phenomenon of visiting Centralia – or what was left of it.

Matt Zullo, a Connecticut student, was visiting with friends. They planned a weekend at a large off-road camping ground in Pennsylvania but decided to drive a long path through the woods of Ashland and onto old Route 61 to give his souped-up Jeep Cherokee a run down the infamous road. Near the bottom, an unrepaired buckling serves today’s off-roaders as a ramp to help get their two-ton four-wheelers some airtime. Matt ran his Cherokee down the road and over-revved, causing slight damage to his front axel – but not enough to ruin their trip.

“We caught enough air to make me never want to approach a jump like that again,” he said with a goofy laugh. It became clear that he and his friends were lifelong off-roaders; he referred their group as “rock crawlers” the way proud fathers will call their child “my kid” – with a tone that they’ve earned it. He also said some of his friends had never been to Centralia, though he clearly had, and he wanted them to see it for themselves.

In his hometown, over 240 miles away, Matt had rebuffed his Jeep with long-arm extension, coated the frame with 3/16” steel and added one-ton steering to it.

“There’s barely a stock part on it,” he said with folded arms and an owner’s accomplishment. “Besides things I’ve had to replace from breaking, there’s probably six, seven grand in there. It’s an ongoing process; I’ve gone through axel shafts, drive shafts…it’s a part of what we do.”

We also met Kathy Davison, a student at the State University of New York’s Geneseo campus. Kathy and Geneseo’s geography club had always been interested in coming to Centralia – not surprisingly – and scheduled a few stops on the way down. The night before, they’d stayed at nearby Locust Lake Campgrounds, equipped with food and tents, and set up camp around a fire pit. Through my interview with Kathy I learned that Centralia’s popularity was growing beyond disaster fanatics.

“I’d always heard about [Centralia] because my dad is a little bit of a geography nerd, and he’s been telling me about it for a while, and then one of our professors actually took some students here for a course and he highly recommended it – said we should check it out.”

By the time we left Route 61 we had seen the vast majority of Centralia and were almost ready to leave. Quick walks through the cemeteries near St. Ignatius Church showed us where the other side of the population had been laid to rest – the Catholics and Methodists.

The next morning we got ourselves ready and Ashleigh drove back home after we made a final sweep of the area. On my way out of Pennsylvania I stopped at the Ashland Public Library and copied most of their archival folder on the mine fire, which was more extensive than I could’ve hoped – most of the newspaper clippings pertaining to the fire pre-dated the internet as we know it today.

We’d confirmed it. Centralia was dead. The brain’s synapses might have been firing, but it would never again hold a parade or raise a child. Most of today’s visitors were like highway drivers rubbernecking at a traffic collision – just trying to get a good angle around the officer to catch a glimpse of something bloody. Others, like Matt and Kathy and us, were coming to pay our respects, collect data and send Centralia off to its maker with a fond farewell. The ride home seemed much faster, as it always does on drives lasting more than an hour or so. My vitality seemed to return with my surroundings, and as I pulled into our driveway, my wife brought the baby out to see me. While I was gone, she learned to clap, and she applauded my return. I brought her a piece of Anthracite.

If any real good has come from the Centralia mine fire, it has perhaps come in the form of Susquehanna University’s geology, biology and chemistry departments. Around the turn of the millennium, Susquehanna U elected to send two members from each of those three departments to Centralia regularly to study it as part of the National Science Foundation’s “Life in Extreme Environments” program. Here, scientists can observe the irregularly-heated, unstable terrain in Centralia and document its habits, which may help prove theories of different periods of life on Earth. Their data on the environment’s effect on local plant and animal life included varying species of weeds and bacteria. A patch of what the group thought was yellow moss was actually sulfur that had crystallized upon contacting oxygen, and the ammonia buildups that have reached the surface proved to kill some microorganisms and provide others with energy sources. The environment of Centralia mimics the beginning of the Earth, which may yet symbolize Centralia’s hopes of rebirth.

Annotated Bibliography

Brown, Nancy Marie. “An Undermined Town.” Research Penn State Dec. 1985: 3-9. Print.

Coleman, Terri. “Boy’s Subsidence Travail on Day of Infamy and Irony.” Pottsville Republican June 2, 1990. Print.

Coleman, Terri. “Centralia Mine Fire Getting Hotter.” Pottsville Republican August 14, 1990: 13. Print.

Coleman, Terri. “DER to Monitor Fire Effects on Ashland Air.” Pottsville Republican Aug. 14, 1990: 17. Print.

Coleman, Terri. “Tourists Ignorant of Possible Danger.” Pottsville Republican 1991. Print.

Coombe, Tom. “Centralia’s ‘Extremes’ Researched.” Pottsville Republican: 1 and 6. Print.

Farrell, Joan. “Centralia Properties Scheduled to be Razed.” Republican Herald 1992. Print.

Farrell, Joan. “Judge Axes Mineral Rights Reimbursement.” Republican Herald. 1 and 12. Print.

GAI Consultants, Inc. Engineering Analysis and Evaluation of the Centralia Mine Fire. Pittsburgh, PA: Office of Surface Mining, 1983. Print.

Karolyi, Anne. “Centralia’s Future: Fire, Smoke.” Pottsville Republican 1991: 1 and 6. Print.

“Landmark Church Scheduled for Wrecking Ball at Centralia.” Associated Press July 29, 1997. Print.

Loughlin, Dan. “Centralia Files Suit for Mineral Rights.” Republican Herald. Print.

Pytak, Stephen J. “Underground Fire Erases Community.” Republican Herald: 7. Print.

Ruane, Miachel E. “Taking a Last Stand in Centralia.” Philadelphia Inquirer June 6 1993: A1. Print.

Usalis, John E. “State Trying to Force out Centralians.” Republican Herald February 1992: 1 and 8. Print.

Thanks

A huge thank you to Jonny Lupsha, who, without your time, effort and dedication to this project, wouldn’t have made any of this photojournalism project possible. A guy that has trusted myself with his work and allowed me to share it with the rest of you on this site.

Without financial backing from people none of this would be possible!

Also my thanks go to Ashleigh Ellis who went through all of this with Jonny and has captured some fantastic pictures for us all.

I wish you both all the luck in the world with your future dreams and ambitions, and hope they all come true.